Part 2 of 3 by John Peatfield

If the first of this series of blogs was about the past of Music for my Mind, then here we shall address – you guessed it – its present.

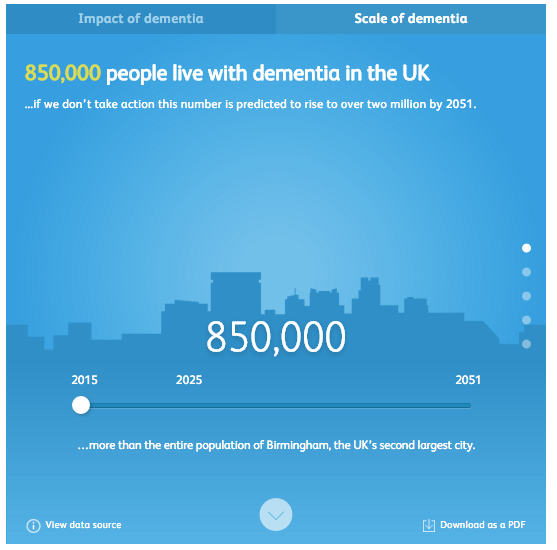

And dementia is indeed, both for those living with it and their families, a very present issue. As we have already seen 850,000 people live with dementia in the UK alone, and of them: 61% feel anxious or depressed, 40% feel lonely or isolated from a community because of their condition, and 52% do not feel sufficiently supported by the Government. With predictions that by 2051 there will be over 2 million people living with dementia in the UK, these issues are only on the increase. But this is now not merely a healthcare problem, but one which does and will continue to severely affect the British economy, with £26.3bn spent on care, predominantly out of the pockets of unpaid carers who are often economically active family members (all stats courtesy of the Alzheimer’s Society.

This is all rather bleak, but there is a light at the end of the tunnel. There are a number of organisations which are trying to solve and allay the severity of the numbers above. Aside from MFMM, there are charities such as Live Music Now, which uses creative music Apps, encouraging care-home residents to become interactively involved in music composition, and Music In Hospitals and Care, which employs professional musicians to perform for residents and display the restorative power of music first hand.

However, there are two distinct obstacles to the great work all of these charities do, the first of which is the hurdle before all the grand plans of life: money. Dementia already costs around £30,000 per person per year, and care programs which can cost anywhere between £200 to £3,400 annually are the first to be cut in already expensive field. Personal Health Budgets (PHBs) and Integrated Personal Commissioning (IPC) can cover some of these costs, but these are often only available to the most severe of cases, and focus more on physical need than mental recuperation. This means that independent charities must cover the costs for musical therapies, using a combination of grants and crowdfunding both to continue existing treatments and research more effective ways of providing care for those living with dementia.

The second obstacle, which despite having a friendlier name is no less formidable, is the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). NICE’s job is to ensure that the standard of care in UK hospitals and care homes is both equal throughout the country and, as they say, excellent. NICE seems rather like a particularly strict teacher, whose intentions and qualifications are beyond question, but who is incredibly hard to convince that you did get that question right and you do deserve that ‘A’. Owing to the limited amount of money the Government, and especially the NHS, has to play with, any new innovation in care must come with irrefutable evidence of triumphant success to justify the expenditure. Thus, for the world of music and dementia care, where much evidence is anecdotal and results are hard to quantify, getting past NICE is fraught with difficulty. Charities can and do operate in care homes, playing music live and through technology in order to care for residents, but to get this to be the standard level of care across the country (MFMM’s major goal) is a task not to be taken lightly.

And yet, we do seem to be moving further down that tunnel towards the sunshine. In 2018 the International Longevity Centre, funded by The Utley Foundation, commissioned a report on the current status of musical therapies in the UK and where they should be, knowing that dementia is a growing issue. Starting with a solid ABBA reference (‘Thank You For The Music’ for those of you who couldn’t guess), the report goes into incredible detail about music, its effects and its use in healthcare. At times it really doesn’t hold fire, talking of ‘devoted advocates operating in a complex and poorly coordinated ecosystem’, but is generally incredibly positive about what is already being done and righteously bellicose about what is left to do. It highlights the ‘promising evidence which is quickly gaining traction’ and demands (thinly veiled under the word ‘recommendations’) new research, new reviews, new postings – including a ‘high profile Ambassador for Music and Dementia’ – and a wave of increased funding and awareness of what music can do for memory loss (7-8).

But where does MFMM fit into this? Although it does often operate in care homes, MFMM, not to blow its own trumpet (but yes, toot toot), is more of an intellectual force. It plans to develop technologies and integrate them into a standard care package available for all (a.k.a. convincing NICE to give us that ‘A’), shown here in their four-point plan:

- To develop cost effective and user-friendly technological solutions to enable rapid creation of personalised playlists for people living with dementia.

- To develop cost effective and user-friendly solutions for the delivery of personalised music in a range of dementia care settings.

- To build the evidence base for the effectiveness of personalised music to improve the quality of life and wellbeing of people living with, or affected by, dementia.

- To promote awareness and take up of personalised music to improve the quality of life of people living with, or affected by, dementia.

Research is the key to progress, and as only £90 of that £30,000 per person annually is spent on research, the work done by MFMM is invaluable for the future of dementia care. The next blog post will go into more detail about this future, but for now it is safe to say that MFMM has its eyes fixed firmly on the end of the tunnel, and can almost feel the warmth of the sun.